Have you ever noticed that natural ecosystems like forests thrive without any added fertilizers? No one has to empty out all the waste from a forest in a green bin, either. These two traits are intimately linked, and they offer a profound lesson for your home landscape or garden. Waste doesn’t really exist in a natural ecosystem. The waste products of species in a forest, say the leaves of a valley oak, fall to the forest floor, where they are then utilized as a resource by the organisms that live in the soil. The leaves are broken down in various processes, their nutrients are exchanged, their carbon is stored, and the soil becomes healthier in the process.

That process is what we’re mimicking when we make and use compost. By composting, we can turn kitchen and yard waste into a nutrient-rich, water-wise, carbon sequestering soil additive. Healthy soil hosts robust and diverse communities of organisms, with a mind-boggling amount of different life forms, and compost helps to support that ecology. A handful of compost likely contains over 10 billion organisms! Plus, following the model of natural ecosystems, we can start to close our resource loops by keeping organic waste within the system of our garden.

Getting Started

If you aren’t sure where to start, you can just start piling organic matter! There’s no one “right” way to compost. The simplest method is a no-fuss pile, ideally somewhere out of the way and in the shade, but with easy access to and from your garden. You can also buy one of many types of manufactured bins or build a bin system yourself. Whichever you choose, the method is mostly the same.

Compost requires four ingredients: nitrogen, carbon, air and water. The easiest technique is to include roughly equal amounts of nitrogen (wet, or “green” material) and carbon (“browns”). Turning your compost pile will introduce more air, which we’ll discuss more below, and water can be added as needed – you want your pile to stay damp, but not soaking wet, like a wrung-out sponge.

Nitrogens include green waste (like grass clippings or freshly cut plant parts), food waste (including brown food waste like coffee grounds), and manure. Carbons include dried materials like wood chips, saw dust, shredded paper, and older plant waste (like dried leaves). You want to avoid any treated wood products, logs or large pieces of wood (which take a long time to decompose), any inorganic materials like metals and plastics, material from diseased plants, and waste from pets or humans. You also want to avoid including meat, bones, dairy, highly processed foods and oils, as they can both attract scavengers and make your pile stink. Whether you include these items or not, you want to bury your food scraps deep in the pile and top them with a layer of carbons to deter unwelcome visitors.

Maintenance

How you tend your compost pile is up to you. You can simply leave it to do its own magic if you aren’t in any hurry, but if you want your compost more quickly (and if you want to kill weed seeds), you can try thermophilic composting, also known as hot composting. Hot composting requires the right balance of greens and browns, proper moisture and aeration, and a minimum pile size of 3’ x 3’ x 3’. You can aerate your pile by turning it with a pitchfork, re-piling it, or even running a PVC pipe into the pile as an air intake. Manual turning is typically done once a week. If your pile is too dry, you can water it as you turn it. During wetter months, you may have to cover your pile to keep it from saturating and becoming soggy. Ideally, when you squeeze a handful of compost, some water droplets should run out. Once your pile has reached optimal size, you may want to start a new pile to allow the process of decomposition to run its course. Hot compost can finish in 2-3 months, whereas the hands-off method can take anywhere from 6 months to a year.

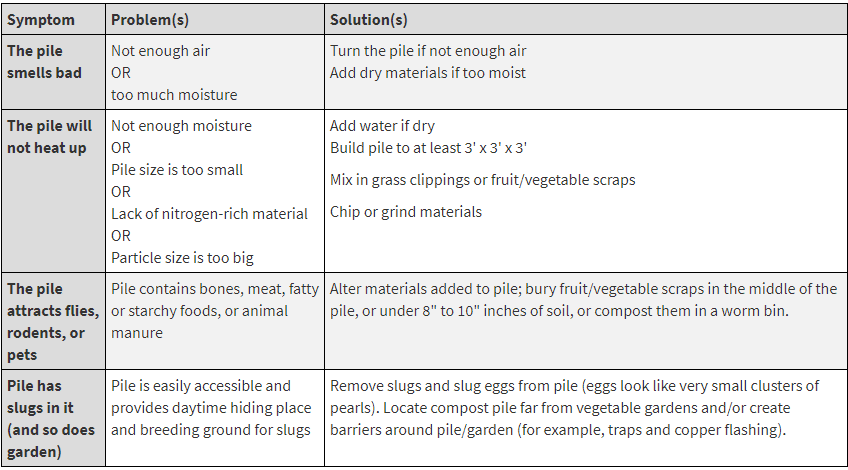

Like any aspect of gardening, don’t expect it to go perfectly right away! You’ll get the hang of it over time. With that in mind here is a handy troubleshooting guide from CalRecycle to help you navigate the process: